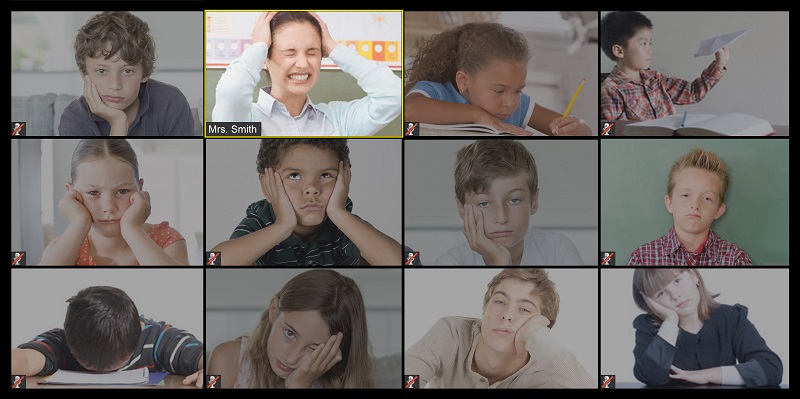

Lockdowns changed education for millions of students, and not always in a good way.

When states closed American schools due to the coronavirus pandemic, state boards of education reacted quickly to ensure that students would continue to learn. Online technologies such as Zoom, for example, were implemented so teachers and students could meet in real time. On the surface, it seemed like the perfect solution. We’ve all seen videos or news clips of a computer screen filled with the faces of eager students hanging on the teacher’s every word. Parents walking into the kitchen were likely reassured to see their child staring into the laptop while the teacher explained the lesson in the background. But the reality paints a much less successful picture of the virtual schoolhouse.

For one, a significant number of students never show up for class—which makes sense, given how much easier it is now to hit the snooze button and grab another couple hours of sleep. Just email your teacher later and explain that your Internet was down.

Another issue is that students trained by our modern education system expect a reward each time they scribble down a word or solve an equation. Teachers today know that if there’s no carrot on that stick, students will shut down.

The Wall Street Journal relays the results of a recent report: “Students have an incentive to ditch digital class, since their work counts for little or nothing. Only 57.9% of school districts do any progress monitoring, the report found. The rest haven’t even set the minimal expectation that teachers review or keep track of the work their students turn in. Homework counts toward students’ final grades in 42% of districts. And some schools that do grade offer students a pass/incomplete.”

This is not only a problem in K-12 schools but also in higher education. Many colleges and universities encouraged their faculty to “go easy” on students this semester. A Columbia University professor this spring had a novel idea: pass everyone. As she admitted, “I wrote to both of my classes a week ago to say that I would give everyone an A based on the work they’d done already.” So much for those students who worked exceptionally hard all semester.

Another study finds that online education has several other downsides. The study mentions that “students without strong academic backgrounds are less likely to persist in fully online courses than in courses that involve personal contact with faculty and other students and when they do persist, they have weaker outcomes.”

Few seem terribly concerned about any of this, especially not the companies that provide platforms for online learning. As one might expect, this is now big business. According to Tech Startups, “[The] coronavirus pandemic is a boon to tech companies offering video conferencing software tools. These companies have seen a meteoric rise in the last five months. For instance, Zoom, a tech company that offers a conferencing app, is now worth more than the world’s 7 biggest airlines combined. Zoom is valued at more than $50 billion.”

Some of this money comes from businesses whose employees work from home during the shutdown, but education makes up a significant part of the total.

None of this suggests that online teaching and learning doesn’t have a place. Online education can replicate on-campus courses to a large degree when done the right way, and for independent and self-motivated learners, it can be a good fit. But we can’t pull millions of young students out of school, sit them down in front of a computer, and expect them to learn as before. Younger children, in particular, need social interaction. They need in-person access to their classmates and their teachers.

When it comes to education, this may be the most important lesson of all.

By

By